Matt Straub

Website: www.mstraub.com

Painter: Brooklyn, NY

“Drop that gun – fast!”

“I’ll drop you first, cowboy!

The action played out between two gunfighters painted on a canvas in Matt Straub’s Brooklyn studio. It was one of a number of canvases – each a recently finished work – that evoked a sentiment of the iconic American West. And although at ten-minute intervals a subway train would rumble in the near distance, reminding us of just how far we were from that era, we really weren’t as far as you might think. Because along with those cowboys on canvases, around the studio were sprinkled other memoirs: a music player filled to the limit with country, western, and rockabilly; old toy pickup trucks made of tin; and hanging above the door, perhaps just as old and weathered, a license plate featuring the iconic Bronco Rider of Wyoming: the state of his birth. And there leaned Matt, up against a table, wearing black Levis smudged thoroughly with paint; a western-style black and white flannel shirt; an unmistakably western silver and gold belt buckle. There was even a windswept quality to his voice that elicited the barrenness and wide-open spaces of the plains, and the toughness needed to survive that environment.

“I’ve been through every state west of the Mississippi – I spent a lot of years hitchhiking out there. I even hopped a few freight trains going through Utah and Colorado, and I suppose people still do that, and hitchhiking’s probably a little more dangerous now. It’s more the local police that are probably going to bother you. It’s a really great way to see the country. You’d see people that, well, they’ve never been more than 50 miles from their house. Or you might run across some crazier guys – people runnin’ out of money and just hell bent.

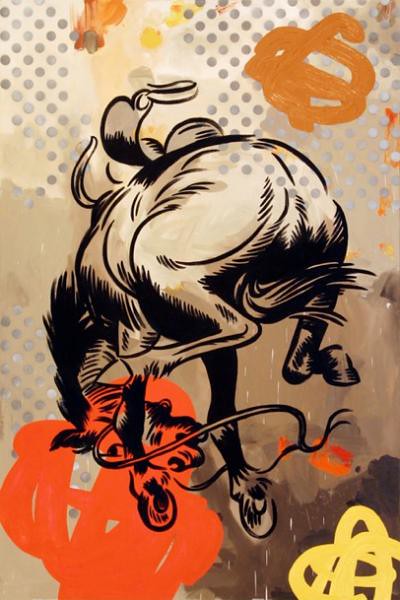

Business for the Undertaker Business for the Undertaker |

I remember one kid that picked us up in North Dakota, I don’t know, he was 16 years old and he was running away from home and had stolen his dad’s car and was just headed out on the road, and well, he gave us a ride for 50 miles, and who knows where his life wound up. But anyway, you get exposed a lot to the harsh landscapes of the West – the badlands and the open plains and the mountains – and you spend a lot of time on the road when you’re hitchhiking. You could be sitting there for three hours, in a desolate area, just waiting for something to happen.”

Take a moment and wonder just how many great American song lyrics and poems must have been penned by those who’ve sat in desolate areas, waiting for something to happen. What a perfect setting for the mind to amble and wander. And if you pay attention to all those pensive moments you’ll have a wealth of information to draw from. It’s certainly evident in the work Matt’s been doing recently.

“It came out of this love of the West, and it’s also a mash-up of all the work I’ve been doing the last 30 years. I was playing in punk bands in the 80s, I lived in Chicago, London, and Berlin, and I traveled to Europe and New York many times, and it was an exciting time for urban-ness and I did a lot of street art and spray paint. But my work has shifted in so many directions in the last 30 years – everything from these really minimal little Zen-like pouring abstractions to figurative things to these more graphic comic things. But there’s a thread that’s always been there. And I’m still using some of those materials. Spray paint is still cheap, fast, and loud. So I keep that all up in my head somewhere. You’re always bringing things back.”

Looks Like Trouble Ahead Looks Like Trouble Ahead |

“I purposely wanted to put this western stuff back in the past, and that’s why I chose this more archaic style and vintage illustration style. I’ve been under the influence of comic books and pulp westerns and old western films, and just using that information as a way of putting the work in more a distant past. Hollywood – and certainly pulp literature – mythologizes and romanticizes and heightens it, and you get some great dialogue and script from that.”

But it ain’t all romance…

“I’m after a little bit more than just a well-crafted nostalgia. There’s certainly that, but I’m also trying to look at the darker side of…you can call it the American dream. It was a pretty lawless and violent place, and certainly very melancholy, too, so you have to be careful about over-romanticizing it. So I’m looking under the hood there and trying to expose some other things. Not that I want to deconstruct the myth at all, but I am kind of exploding it, imploding it, seeing what happens.”

Look at the swirls of paint – the way they intrude the scene. You can’t help but feel the tension that much more. And it’s the drips of paint. The heaps of paint. Sometimes it’s so heavy you can see the brush marks. Matt is pushing how many layers he can add, how much of a discord he can generate. It’s such a commotion of feelings – that unsettling combination of the cold reality of the old West with the warm nostalgia of how it was portrayed in American film and literature. Think about it: even though many of the speech bubbles in Matt’s work are lacking words, you can ultimately fill in the blanks, can’t you? The cowboys and cowgirls of the old West still influence today’s America.

Buzzard Bait Buzzard Bait |

I wondered what a cowboy from one of Matt’s paintings would say to a street thug like the one in that newspaper.

‘Not fast enough, buzzard bait!’

“It is still the wild West out there. There’s plenty of… I don’t know if they’re really gunfights – a lot of the slaughter going on is pretty much one guy with a gun. Not exactly fair fights.”

The West is fading, after all…

“You see these ghost signs in New York on the sides of buildings – these old, faded advertisements that are just barely there – and we get a lot of those ghost signs out West, too. I like to say this work is kind of a ghost sign, too. Because yeah, there is that intrusion of the modern on the Western landscape, and hey, it’s always changing and you can’t be too nostalgic for it. The West has really changed a lot. There’s a faint history left, and well, how much truth was in that in the first place anyway, because of the romanticization? It was a pretty difficult place to live, and a pretty tough life – a short, quick life for a lot of people. But the wide-open spaces, they’re still there, they still viscerally move people.”

That notion stems from the mind of a true artist, doesn’t it? It’s a keen sense for what’s changing, and what’s lasting. And what’s important. The ability to see things unfiltered. The desire to move people with art.

Ghost 3 Ghost 3 |

“I think paintings are still really important because it’s about this visual language. It’s a language that’s only good for painting. It’s a purely visual thing. You can’t verbalize it, and that’s why paintings can suck you in and you can study the surface and little drips and small passages of well-painted areas. People can just spend a lot of time looking at them.”

It’s that feeling of paint. Actual paint. On an actual canvas. The texture of it. Get close enough and you’ll probably even catch a scent of it. As for a digital image? It just won’t give you that same experience. So it’s well worth making the effort to get to a gallery. After all, the skill of creating an evocative painting and a one-of-a-kind message is something that can take a painter years to develop.

“You have to remember how at one time everybody hated the impressionists, and now everybody’s grandma loves them. It was just the start of this wild, insane stuff at the time, and it’s people like Cézanne or van Gogh, I mean, they developed this visual language of their own, and that’s what all artists are trying to do. The problem is your language may be so incoherent nobody really gets it, and that’s why art can be a lifelong project trying to refine those things.

I think most people who have given up art – it’s only because they haven’t really worked hard enough, and you realize it might take you 10, 20, 30 years to really push it, push it, push it ‘til you’ve got something interesting. It takes a lot of devotion, maybe some sacrifice along the way, but you could be painting in the studio and you look at the painting on the wall – just on a cloudy day versus a sunny day versus artificial light – the painting is always gonna look different. Different things are going to happen. I find if you work a day in the studio and then you walk outside, all of a sudden things are more vibrant out there.”

Chugwater Chugwater |

“What I really notice is contemporary society spends a lot of time getting out of the moment. You’ve got headphones in your head, you’re listening to music, and you’re emailing, and all of that is getting you out of some moment and allowing you to be somewhere else. That can have some value and some interest on it, but artwork kind of forces you to look at something for, you know, at least 20 seconds, and I think that moment of observation and contemplation is really necessary. Our society now seems to have this fear of being in that moment. Every electronic device is designed to get you out of that moment.

And I think humans are good at absorbing input; right now it just happens to be this electronic input. I mean, I listen to music in my studio, but I don’t need it walking around on the street. There’s an awful lot going on out there. There already is the natural soundtrack, which is pretty interesting.”

That statement came just in time for another subway train to rattle wearily past the studio. And although the soundtrack of the city that day might have been quite different from that of the old West, if you were to walk along some of the nearby cobblestone streets toward the East River you might gather that if there’s one thing Brooklyn and the old West do have in common, it’s that time changes everything.

“That rust and that decay and those ghost signs – I’m just really attracted to things that have aged that way. And maybe the West is like that, too, because between the wind and erosion, nature does wipe a lot of it away. But there are also still places where you can see where the Oregon Trail wagons went across – the ruts in the road are still there 150 years later, even more. So there is that fragility as well as the toughness. Nature’s really tough. I mean, you’re up in the mountains, there are tough storms. It’s potentially a very dangerous place to be. It’s harsh. But that harshness and the beauty are partnered together, and that is the sublime.”

The End The End |

{november 2012}(images c/o Matt Straub)

All stories are copyright of Gregory Koutrouby and A Thousand Stories unless otherwise noted.